Part 1 of ‘Imagining Urban Futures of Tamil Nadu’ series

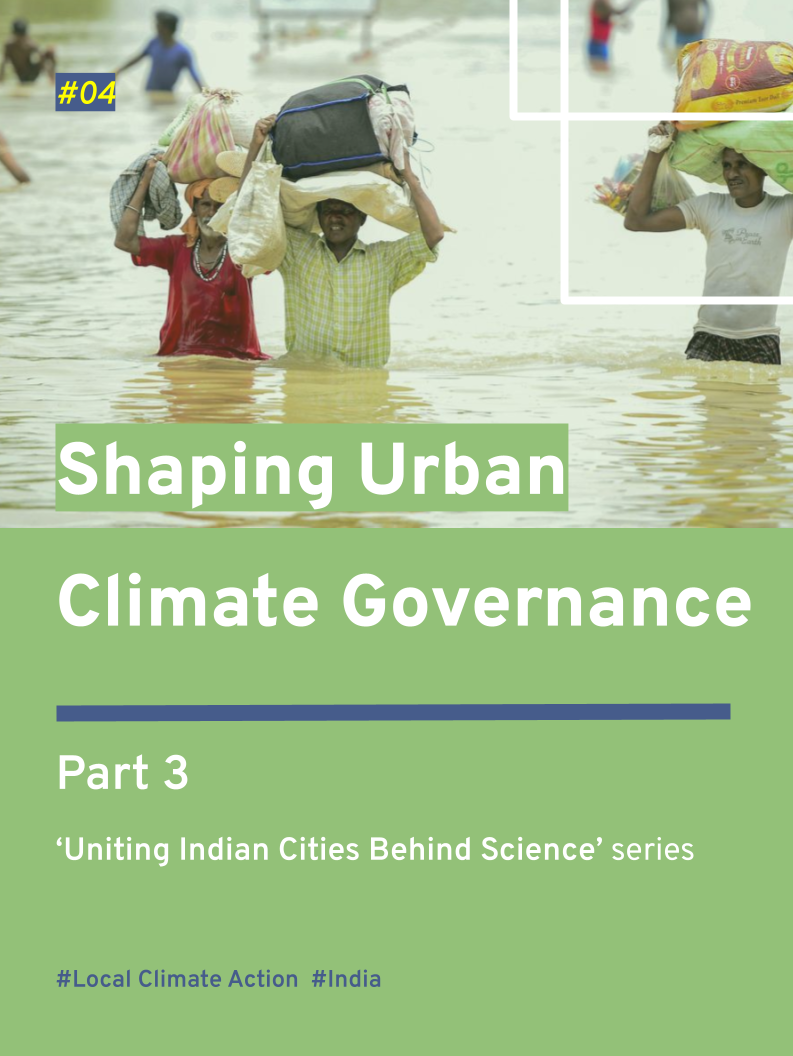

Chennai, Tamil Nadu (TN), India, during cyclone Michaung in 2023 (Source: AFP)

"So climate change does not need some shiny new movement that will magically succeed where others failed....climate change can be the force—the grand push—that will bring together all of these still living [social, labor, and environmental] movements.", highlighted Naomi Klein in her book ‘This Changes Everything’ (2014). I am interested in exploring and imagining, “How will this force shape the cities of Tamil Nadu; a coastal state in India?.”

Cities are the sites of new, complex, and interconnected spatial and social networks. From the Garden City movement of the early 20th century to modern-day Low Emission Zones, the core idea is to reduce the impact on the environment and create value for human life. But researchers suggest that three unique contextual characteristics of today’s world set our approach to city-making apart from that of the early twentieth century: the neo-liberal economic system, international diplomacy led by climate science, and growing geospatial connectedness at the planetary scale.

Maybe, to imagine Tamil Nadu’s urbanism trajectory (or any region’s), we need a new thinking and doing lens to support and challenge this new system, science, and scale. So, before we discuss the socio-politics and spatial narratives of Tamil Nadu, let's look deeper into this 'need for a new lens'.

The academic world has observed this need and begun debates around framing ‘Climate Urbanism’ as an influential idea for imagining our futures. By Eugene McCann’s definition of urbanism, climate urbanism can be interpreted as how urban life is defined and understood in today’s climate crisis, alongside the different ways of intervening in cities to tackle them. The wave of sustainable urbanism or sustainable urban development, used as an umbrella term to guide and capture the policy and planning initiatives of the past three decades, is now slowly receding, to be superseded by climate urbanism.

To get closer to shaping climate urbanism as the ‘new thinking and doing lens’, let’s decode the three characteristic actions that define them covering the economic system, science-led diplomacy, and planetary scale.

1. Protecting Urban Economic Systems

‘We must protect our cities from the climate crisis’, is an established and accepted international agenda. Making this the foundation, climate urbanism’s simple argument is that protecting cities needs low-carbon, resilient infrastructure, which requires significant investments; therefore, we must promote economic growth, financialization, and privatisation, standing by the global neo-liberal order.

A development model that is driven to expand future economic growth to protect the present economic capacity could lead to speculative, competitive, and exclusionary urbanisation processes, says Linda Shi in her contribution to the book 'Climate Urbanism: Towards a Critical Research Agenda (2020)'. This emphasises climate urbanism’s growing inclination to protect and expand infrastructure through market-led financial mechanisms and the risk of shaping climate action as a constituent part of capitalism.

That’s interesting! From now on, we shouldn’t consider capitalism as ‘the’ problem for the climate crisis, but instead the reason and the means to solve it.

2. Placing Climate Science at the Centre of Diplomacy

Climate urbanism’s foundation is in the emerging climate findings, and a key feature is carbon management. The aggressive mainstreaming of GHG inventories at the regional or city level places the process of measuring, monitoring, and managing carbon as the central object of local policies, programmes, and politics. The academic journal ‘From Sustainable Urbanism to Climate Urbanism’ suggests three implications of this carbon-centred global diplomacy. Firstly, the one-dimensional carbon narrative has simplified public communication on climate policies. Secondly, this has enabled governments to come up with straightforward, targeted carbon reduction strategies, as opposed to the earlier challenges in devising and implementing multi-faceted sustainable development initiatives. Thirdly, it has also led to thinking about climate governance at the urban scale and nudging behavioural change at the institutional or individual level.

This is true. In 2023, nearly 1000 cities reported to the Carbon Disclosure Project, of which almost 100 cities have a Climate Action Plan with carbon targets. So, we can hope all we care about right now is 'reducing carbon’ and nothing else matters. Also, cities know what they should be doing, and only doing it is pending.

3. Recognising spatial influences at the planetary scale

Planetary urbanisation as a theory breaks the urban-rural distinction and brings territories that lie well beyond the traditional city cores and suburban peripheries as part of the urban fabric through the shared socio-economic and ecological processes of the 21st-century neoliberal world. With the growing momentum for local climate action, this offers a new (planetary) scale for engagement in urban theory and policy and suggests the need to approach the global urbanisation process as a planetary whole and a network of cities.

Our boundaries are blurred. Yes, especially because the impact of carbon has no boundaries. With the advanced climate science findings, we now know that a few tonnes of additional emissions in Thoothukudi, a small coastal city in Tamil Nadu, will stay in the atmosphere for 300-1000 years and likely contribute to an increase in average global temperature. Hence, additional emissions are not just a Thoothukudi-only problem but the entire planet’s.

Living at a crucial moment in earth’s history that prioritises cities as sites for climate action, exploring the urban futures of Tamil Nadu—the second most urbanised state, with the second longest (1,076 km) coastline in the country, and a high climate vulnerability index score—requires contextual sensitivity and creativity.

The blogs in this series will bring in both of those to draw patterns and possibilities for imagining the coastal state’s trajectories of urbanisation.

Have questions, thoughts, or feedback? Write to nagendran.bala.m@gmail.com.