Part 1 of ‘Climate Policies and Instruments’ series

Photo showing the installation of solar panels on rooftops on private houses in Germany (Source: AP Photo/Martin Meissner)

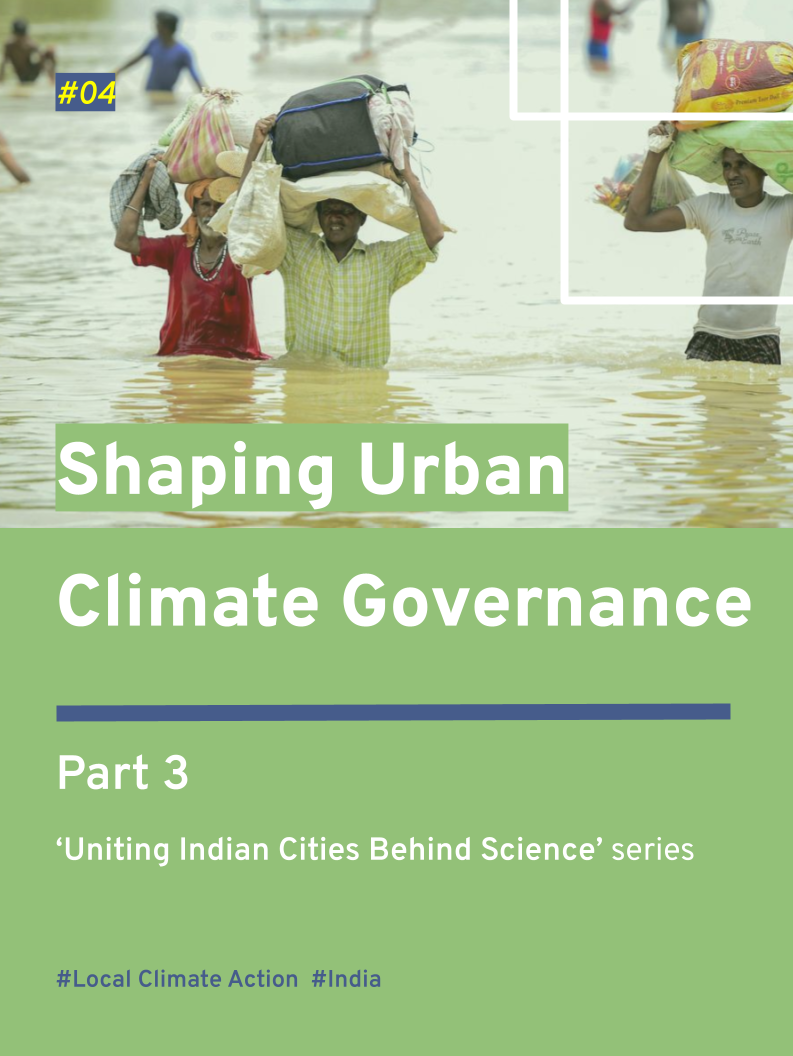

The Sustainable Development Goal 7, to “ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all,” is at the centre of global climate conversations, as energy transition from polluting fossil fuels to renewables is set to alter the global geopolitics. Tracking SDG7: The Energy Progress Report, 2024 suggests that the energy access gap has worsened globally with an increase in population growth, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, leading to 685 million people living without electricity in 2022. While the Global South has severe challenges in providing new connections, the Global North is left with the challenges of transitioning to clean and efficient energy. In either case, a right policy instrument is key to enabling a low-cost and just transition.

From this background, this blog series will explore the various governance tools being employed to accelerate energy transition, starting with Germany’s Building Energy Act, 2023, in this and the next blog.

Introduction: What is Germany’s Building Energy Act, 2023?

Germany's recently amended Building Energy Act (GEG, 2023), which came into force on January 1, 2024, aims to modernise buildings' heating systems. As an emergency legal move to reduce the current 15% emissions contribution from the country’s building sector, the law is designed as a non-market-based, ‘command-and-control’ (CAC) policy instrument for climate mitigation. The European Environment Agency defines CAC as “mechanisms, laws, and measures that rely on prescribing rules and standards, and using sanctions to enforce compliance with them”. The GEG, 2023, prescribes a specific rule, to transition all buildings to district heating services, solar thermal systems, or other forms of renewable energy-based heat pumps, including biomass, hydrogen, biomethane, or any approved environmentally friendly source, by 2045. It also imposes a de facto ban on installing new gas- and oil-based systems. The law recommends a technology standard mandating that almost all newly installed systems should run on a minimum of 65% renewable energy. Property owners failing to abide could face penalties of €5,000–€50,000.

The law also proposes a range of exemptions and subsidies. The elderly, who are over 80 years, own a flat or building with up to six flats would get a waiver from this mandate. Every property owner is eligible for a basic 10–40% subsidy for each heating system. In addition, three other climate bonuses are also available, covering: 1) a 5% efficiency bonus for installing high-quality, low-emission equipment; 2) a 20% climate speed bonus until December 31, 2028, to replace high-emission heating facilities that are more than twenty years old; and 3) a 39% income bonus for families living on their property with taxable income lower than €40,000. In total, a payback of up to 70% for replacing heating systems in existing buildings has been promised.

Greenpeace, a climate campaigning organisation, called it "a long overdue milestone," while Germany’s Free Democratic Party criticised, calling it the “equivalent of an atomic bomb for Germany.” While these are the remarks from environmental and socio-political perspectives, how do CACs perform from a climate policy and economics perspective? In this blog, let’s start with understanding CACs.

Image of protesters demonstrating against Germany’s proposed Building Energy Act in Munich (2023) - Read the full news article here.

Command and Control Instruments: What are they?

Environmental legislation passed across the world in the early to mid-twentieth century—Alkali Works Regulation Act (1906), United Kingdom; Clean Air Act (1963), United States of America; Environmental Action Programme (1973), European Union—predominantly falls under the CAC category. While market-based instruments have become popular in the last few decades, research shows that a significant share of climate policies targeted to reduce household emissions include CAC instruments, in high-income countries, including Germany.

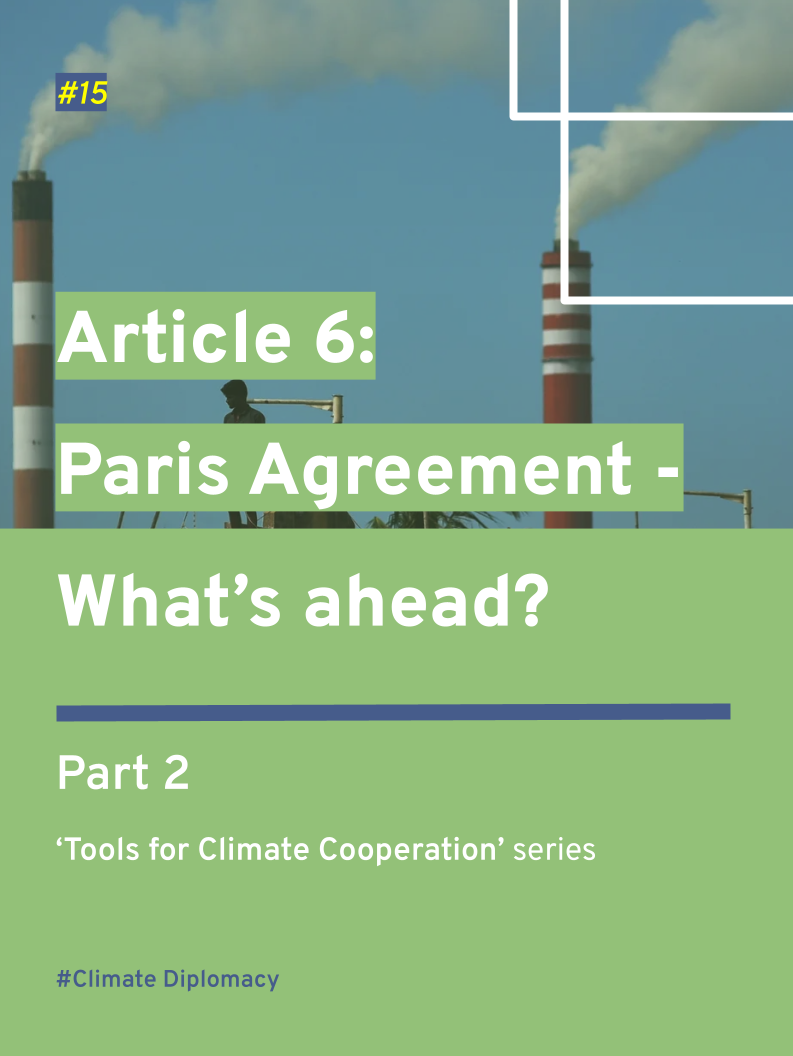

Illustration showing the sectoral share of command-and-control and market-based climate policies (n=250) for household decarbonisation in four high-income countries (Sweden, Norway, Germany, and France)

CAC policies typically prescribe one or a combination of ambient, emission, and technology standards. The GEG 2023 follows the technology standard route by setting the 65% renewable energy benchmark for running heating systems and encouraging property owners (polluters) to (partially) pay the cost of pollution (by replacing with or installing a cleaner system). The role of a climate policy is twofold: 1) accelerate action and impact at a higher pace than the status quo, and 2) do that in a cost-effective way for society. The strengths and weaknesses of CACs are also dependent on their capacity to balance both of these needs and achieve an equitable and inclusive transition.

For example, let’s imagine your home consumes 100 units of electricity for heating, and almost all of them come from a gas-based system, which is likely to work fine for the next 25 years. As long as it is working fine, you will not be motivated to replace them, though your consumption and emissions may increase in the coming years. Hence, the role of climate policies is to make sure less-polluting, high-efficiency alternatives are available in the market, they are accessible and attractive for you to replace your existing system earlier than 25 years, and this transition happens at the lowest cost possible for you and the society.

Does the Germany’s Building Energy Act, 2023 balance these as a CAC instrument? - Check out the next blog.

Have questions, thoughts, or feedback? Write to nagendran.bala.m@gmail.com.