Part 2 of ‘City and Cinema’ series

View of Dhobi Ghat in Mumbai (Source: Dennis Jarvis, Encyclopaedia Britannica)

I recently had the chance to watch the trailer for 'Mumbaikar', a Bollywood movie released in 2023, which is a remake of the critically acclaimed Tamil film 'Maanagaram (2017)'. As a big fan of 'Maanagaram' as a movie and a hyperlinked story that captured the social nuances that make Chennai a metropolitan city through diverse characters, I couldn’t accept the possibility of placing the same story in a different urbanscape, Mumbai (previously called Bombay).

Why do creators do this? Why? Is Mumbai out of stories to tell, and we are forced to borrow from other cities? Or are the stories of metropolitan cities so generic today that the creators think the same plot could be placed in any comparable context? These questions make me wonder if this cinematic remake approach is equivalent to a 21st-century architect’s urge to place a glass building on any plot.

Anyway, leaving aside my disappointment in the 'Mumbaikar’s' trailer, I took this as a nudge to revisit an essay I wrote five years ago on movies set in Mumbai and make it a 2-part blog series. This is Part 2, which discusses the cinematic spaces of four movies staged in Mumbai from the previous decades; Salaam Bombay (1988) - Mira Nair, Bombay (1995) - Mani Ratnam, Slumdog Millionaire (2008) - Danny Boyle, The Lunch Box (2013) - Ritesh Batra)

Click here to read Part 1 that sets the premise for the discussion here.

In India, city life constantly acknowledges and draws parallels to its rural counterpoint—both as a place of peace and pressure—and that is explicit through the cinematic conceptions of spaces in these movies. The scenes from the films 'Salaam Bombay (1988)' and 'Slumdog Millionaire (2008)' display how one cannot distinguish the character of the city streets as urban or rural, as distinctive meanings and purposes are added based on how people use these spaces.

City streets as spaces for everything including washing clothes and everyone including cows

Urban vs. Rural:

Besides, the aspiration or association of the characters from a more rural or semi-urban background also inscribes strength to the blurred meaning of urban space and its narrative. In 'Bombay (1995)', for instance, the protagonists Sekar and Banu from a rural background are placed between the conflicts of rural and urban ideologies over religion and the consecutive reactions to it in their lives. The narrative puts forth the larger conflict and religion-based riots in Mumbai and the relational conflict between the parents of Sekar and Banu at Tirunelveli as problems of the same content but of different scale and setup. Similarly, in 'Salaam Bombay (1988)', the lead character, Krishna, or Chaipau, throughout the movie aspires to return to his village with the money that he is supposed to earn. His departure from the city is what has been told all along as the notional climax of the movie itself.

Through these attempts to put forth the conflicts of the city as a macrocosm of what one sees in villages (as in the case of 'Bombay') or as a never-ending phenomenon that urges people to move out as soon as their purpose or cause is satisfied (as in 'Salaam Bombay'), the movies also question the idea of modernity and cosmopolitanism, the common labels we associate cities with. In a larger sense, it questions the constructs of rural and urban as highly accorded as avenues for opportunities and to escape from reality. While Sekar in Bombay never wants to return to the village, Chaipau in Salaam Bombay has been counting his days to return to his village. For one, it is a place of peace; for another, it is one of pressure.

Urban as a macrocosm of rural through the frames of 'Bombay (1995)'

The Arrival:

The spatial conception is also a by-product of how the play of the lens (camera) and scissors (editing) is articulated. The movement of the camera, its speed, distance, focus, colour, transition, continuation, and placement determine the connection it establishes with the city and the characters involved. Editing brings life through sequencing and control of timing.

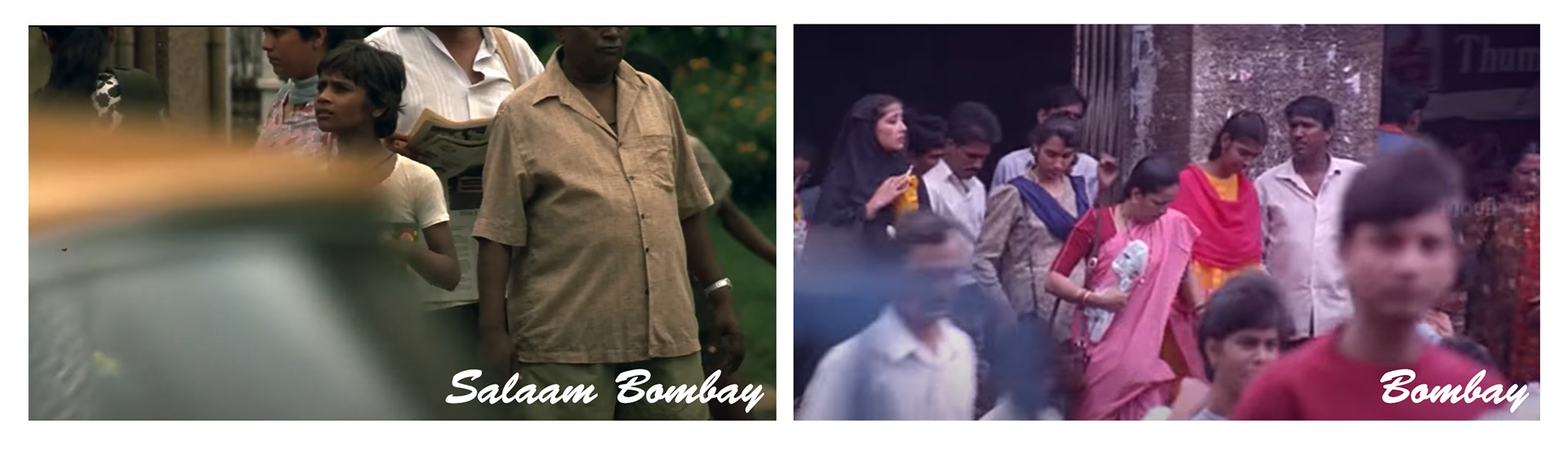

In ‘Bombay (1995)’ and ‘Salaam Bombay (1988)’, the idea of placing the characters on the other side of the road and letting actions of the city happen between the camera and the actors allows the exaggeration of city chaos in which the protagonist is just a part. Whereas in their introduction shots at respective villages, the protagonists were put in front of the camera with the vast green landscape spreading as the background. In an urban setting, the characters are a speck of a messy whole, whereas in their rural context, they carry a distinct identity and takes the centre stage.

The arrival of protagonists - Urban setting

The arrival of protagonists - Rural setting

Building Narratives:

In 'The Lunch Box (2013)', the story has two layers of protagonists: Sajan Fernandez and Ila in the dominant layer, and the Tiffin Box itself in the subordinate layer. Among these, Ila becomes the passive character with less motion, whereas the travel of Sajan and the Tiffin Box have been presented as overlapping sequences of similar value, which indicates the long journey that they were forced to take in the city.

In 'Bombay (1995)', the picturization of riots also becomes crucial as the camera runs along with the common crowd, capturing the fear, speed, and intensity of the action and their effects on the city. The lens also strategically pauses the protagonist’s reaction to loss and search at regular intervals. This tries to narrate the story as the story of the city and the story of Sekar and Banu, framing the commotion and emotion simultaneously.

A similar narrative technique could be seen in 'Slumdog Millionaire’s (2008)' catch-and-run sequence between Jamal, his friends, and a group of cops, as they were found playing cricket on private land. The long-cut shots introduce to us both the filthy, dull, and swampy Dharavi and the mischievous, energetic, and joyous Jamal with his brother; contra-distinction of the space and its people.

Slumdog Millionaire (2008) capturing the story from the perspectives of space and people.

Elements and Symbols:

A place or a region, irrespective of its scale, is visually or culturally coupled with multiple, yet unified, elements and symbols. Anchoring the character and the screenscape to these elements and symbols not only supports the visual narrative but supplements the associational values of the viewer to enable quick recognition of space and tie a memory knot.

In 'Bombay (1995)' and 'Salaam Bombay (1988)', the characters arrive at the land from a long distance, and they are alien to its urban form and grandeur. This conjunction is demonstrated by placing them at the famous Chhatrapati Shivaji railway terminus on their landing. This introduces the city not only to the characters but also to the audience.

In depicting the daily life scenes of Saajan in the city, 'The Lunch Box (2013)' sheds light on the lifeless local train journey that covers his monotonous everyday experience. Finally, his journey continues with the dabbawalas, though his journey with Ila’s dabhas might have ended there. Only this final journey in the movie captures Saajan with light and life.

The Bogies as the lifeline of Bombay and 'The Lunch Box (2013)'

‘Bombay (1995)’ captures the nuances of urban life where the idea of marriage just gets over in registration, there is no one to question the public display of affection, and life in chawls with multiple tenements is the only choice. In contrast to all this, the subtle irony of identifying humans with religion existed in both spaces. The reactions were the same when both Narayana Pillai (Sekar’s father) in Tirunelveli and the house owner lady in Mumbai heard Shaila Banu’s name at first.

What’s in a name? - Bombay (1995)

In 'The Lunch Box (2013)', the travels of Saajan’s lunch box in the introduction sequence present the context for the movie and the city. The sequence of actions that are involved is captured in detail, with attention given to the hands that are involved in this lunch box delivery and return system. From the kitchen to the work desk and back again from the office lobby to the doorstep of the home, the travel of the lunch box, for that matter, is more lively than the travel of Saajan.

The Hot Urban Journey - 'The Lunch Box (2013)'

Carving out the climax or saving up something for the end is the most thought-out section in all four movies, as they end at a city event or a landmark. 'Salaam Bombay (1988)', captures the festivity of the city and stages its climax on the eve of Ganesh Chaturthi. 'Bombay’s (1995)' climax calls for peace in the event of chaos and riots. 'The Lunch Box (2013)' settles down on another train journey. 'Slumdog Millionaire (2008)' builds up the pressure on the traffic jam on the streets and ends it well at the railway terminal.

Our cities are seen, understood, and experienced through a medium of art (cinema) that, in its terms, has subjectivities in conception and expression. The connection between lived experiences and cinema takes differences through the layers projected and hidden. The urban experiences of hope and loss, yearning and nostalgia, terror and fear, the mapping of identity and difference, and the spectacles of contemporary consumption are all explicit through the cinemas of Mumbai, which borrow urban life as a story, record instances, and leave a new reference for the future.

Let's wait for a new story that represents Mumbai in this decade with honesty and ingenuity!

Have questions, thoughts, or feedback? Write to nagendran.bala.m@gmail.com.

This piece was originally published as an essay in 'City Observer Vol 6: Issue 2, a biannual journal on cities, published by the Urban Design Collective.'

Reference:

Bombay cinema – an archive of the city, Ranjani Mazumdar (2007)

The Cinematic city, David Clarke

Cinema and invention of modern life, Giuliana Bruno and Leo Charney (1993)